Deep-Sea Mining Test Impacts Biodiversity, Study Finds

Independent research links localized seabed disruption to experimental deep-sea mining, fueling a heated debate over minerals for clean energy and the health of ocean ecosystems worldwide.

Leading scientists have completed the largest independent assessment of test mining in the deep ocean. The study reports clear harm to seabed life within the mined corridor, underscoring the environmental trade-offs of harvesting minerals for green technologies.

The researchers compared biodiversity two years before mining with two months after the test operations, which covered about 80 kilometers of the seafloor in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean.

The project was led by scientists from the Natural History Museum in London, the UK National Oceanography Centre and the University of Gothenburg, and was commissioned by the deep-sea mining company The Metals Company. The research was conducted independently, with the company allowed to view results before publication but not to alter them.

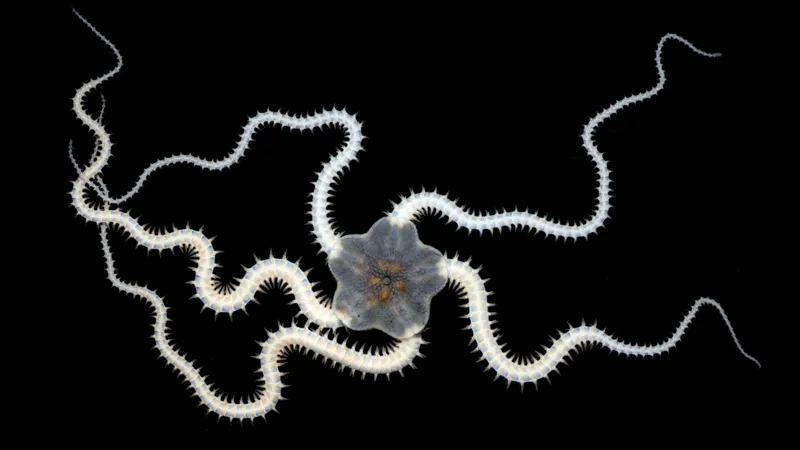

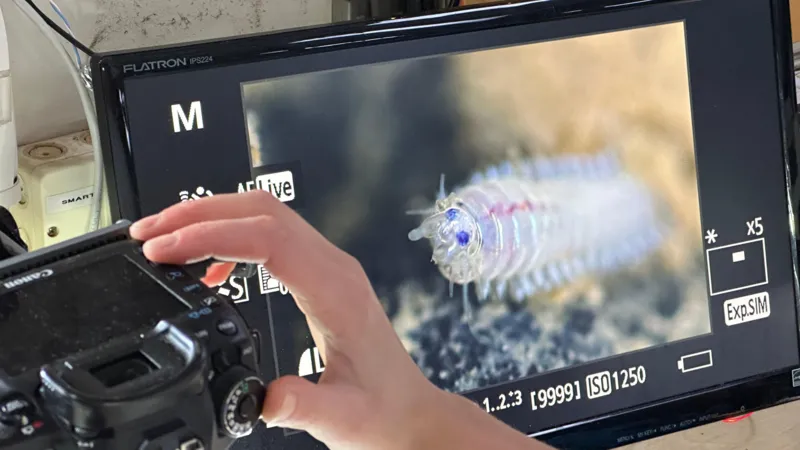

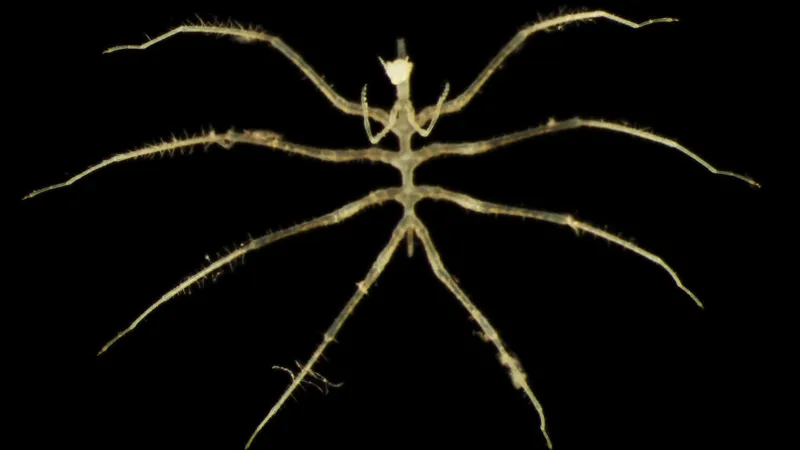

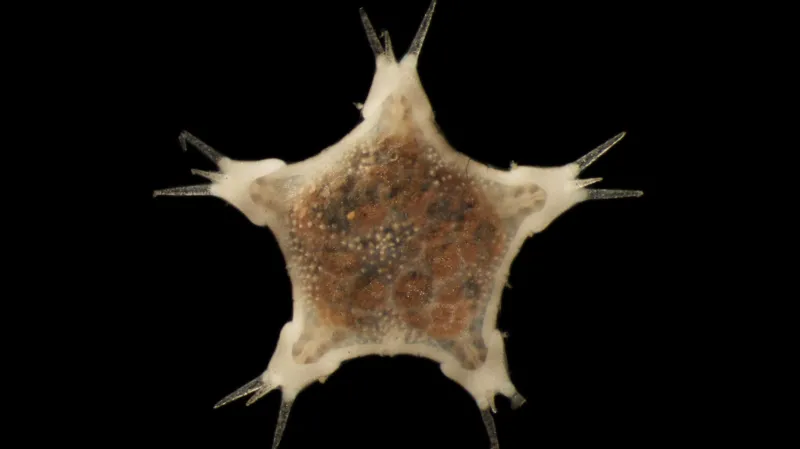

The team focused on small animals ranging from 0.3 millimeters to 2 centimeters, including worms, sea spiders, snails and clams.

Key findings

- Abundance decline — In the vehicle tracks, the number of animals dropped by 37% compared with untouched areas.

- Species diversity — Biodiversity declined by 32% in mined zones.

- New discoveries — More than 4,000 animals were found, about 90% of which are new species.

- Sediment removal — The mining process removes the top five centimeters of sediment, where most seabed life resides.

Lead author Eva Stewart, a PhD student at the Natural History Museum and the University of Southampton, explained that taking away sediment directly reduces habitat and food for many species.

Dr Guadalupe Bribiesca-Contreras from the National Oceanography Centre noted that mining-related pollution could slowly threaten more vulnerable species. Some animals may move away, but it remains unclear whether they will return after disturbance.

Near the tracks, where sediment clouds settled, the overall animal count did not drop, but the community composition shifted toward different species.

Adrian Glover from the Natural History Museum described the results as cautiously encouraging, suggesting limited wider impacts within the tested area.

A spokesperson for The Metals Company said the data indicate biodiversity impacts are confined to the mined zone. However, several experts warn that larger, commercial operations could pose greater ecological risks.

The study takes place in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a vast area in the Pacific Ocean believed to contain billions of tonnes of nickel, cobalt and copper-rich nodules. These minerals are critical for renewable energy technologies like solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles, and demand is expected to grow substantially by 2040. While the International Seabed Authority has not approved commercial mining, it has granted exploration licenses, and many countries call for a precautionary pause.

Scientists emphasize that current mining methods are too harmful for broad, commercial use, and they urge the development of less invasive techniques if deep-sea resource extraction is to continue. The findings appear in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Key takeaway: Biodiversity impacts from deep-sea mining in this test appear localized to the mined area, underscoring the need for careful technology development and policy safeguards. Source: BBC News